News

State Leaders Outline 2026 Priorities with Major Implications for Cities

In remarks delivered during the Georgia Chamber of Commerce's January 14 "Eggs and Issues" breakfast, state leaders outlined a broad agenda for the 2026 legislative session centered on affordability, infrastructure, workforce development and economic stability; all areas with direct implications for Georgia’s cities.

12 Georgia Cities Receive Federal Funding for Road Safety Projects

Twelve Georgia cities are among the recipients of more than $54 million in federal funding awarded statewide to improve roadway safety for drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists. The funding comes from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) program.

Next Generation 9-1-1 Study Committee Releases Final Report

The House Study Committee on Funding for Next Generation 9-1-1 has released its final report outlining recommendations to help Georgia transition from a legacy 9-1-1 system to a modern NG911 platform, with a planned statewide launch around 2028.

Viewpoints

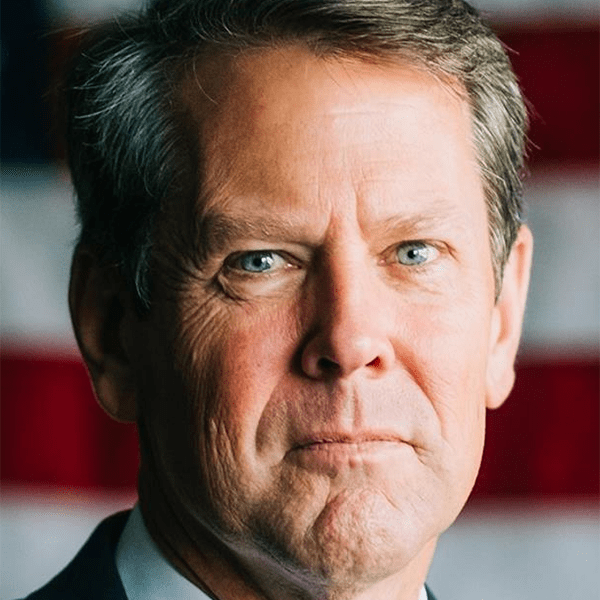

Gov. Kemp's 2026 State of the State Address

Text of Gov. Brian Kemp's 2026 State of the State address delivered on January 15, 2026.

Loving Our Cities: Why It Matters Now

"If we want stronger communities, healthier civic life, and a more prosperous state, we need to recover the idea that cities aren’t just places we live; they’re places we love."

Georgia’s Cities Magazine

Columns & Features in the Q4—October Issue of Georgia's Cities

- Finding Common Ground for the Common Good

- Looking Up

- Making Tourism Georgia’s Top Industry: A Legislative Outlook

- Reducing Accidents, Reducing Premiums

- And More…

If you are a local official or staff member of a GMA member municipality and are not receiving the magazine, please complete the Georgia’s Cities Magazine Subscription Preference Form to be added to the subscription list.