Knowledge Center

How Quality Child Care Translates into an Economic Development Tool

Columbus Mayor Skip Henderson didn't always see child care as an economic issue, but now the city is taking concrete steps to make quality child care more affordable and accessible for working families.

2026 ARPA Reporting Guide & FAQ

As the April 30, 2026 annual reporting deadline for the American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA) State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) approaches, many local governments have questions about the report and how to best prepare. This guide and frequently asked questions assists cities with the reporting process.

New Guides Help Cities Engage Young People in Civic Life

GeorgiaForward recently released two guides to help cities connect young people with civic life as part of the America250 celebration. In this Q&A, GeorgiaForward Managing Director Sadie Krawczyk talks about what's in the guides and how cities can put them to use.

Handbook for Mayors and Councilmemebrs

Handbook for Mayors and Councilmembers

Every year, local government becomes more complex, and local leaders must address challenges including legislative and regulatory changes, scarce resources and increased service demands, workforce development needs, and rapidly evolving technology. At the same time, city officials strive to implement innovative programs and foster smart, livable communities and maintain their city’s unique character and sense of place.

Governance & Policy Making

Handbook for Mayors and Councilmemebrs

Suspension and Removal of Elected Officials

Covers the procedures for suspending and removing Georgia municipal elected officials, including grand jury indictment, felony conviction, and recall by electors under the Recall Act of 1989.

Ethics & Transparency

Handbook for Mayors and Councilmemebrs

Ethics, Conflict of Interest, and Abuse of Office

Covers the ethical and legal obligations facing Georgia municipal officials, including conflicts of interest, bribery, abuse of office, campaign finance disclosure, and zoning conflicts. Also addresses GMA's Certified City of Ethics program and applicable federal laws.

Information Technology & Cybersecurity

Article

Top AI Investments Municipalities Should Budget for in 2026

February 24, 2026

Municipalities should budget for seven essential AI areas in 2026, along with an AI readiness assessment. These seven areas include licensing for AI productivity tools, AI enhanced cybersecurity, data analytics and governance, resident facing chatbots, AI integrations within existing systems, staff training, and pilot funding for future use cases.

Housing

Data Dashboard

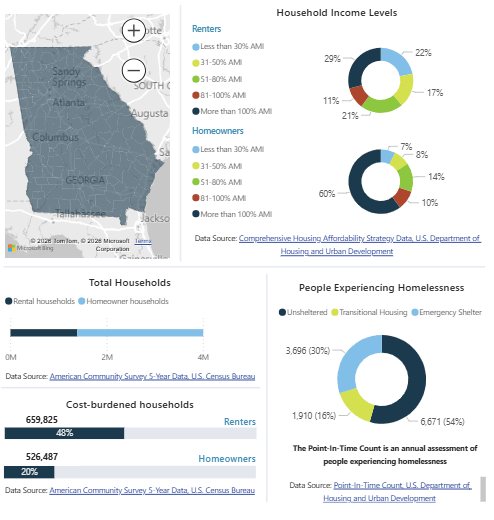

Housing Development Needs Dashboard

The DCA Housing Development Need Dashboard is an interactive platform to explore housing data on county- and on a regional-commission-level.